Waqf Habitat in Cyprus: a Review of Sefer Soydar’s Talk

Waqfs in Cyprus have recently attracted historians’ attention in an ever-increasing manner. The number of new articles, books and theses that came out in the last few years suffice to show the abundance of research about this specific theme. At first glance, such a trend seems perfectly clear and reasonable given the significant historical role that waqfs played in the island’s history in economic, social and cultural terms. Yet, historical research, especially in or on conflict-ridden areas like Cyprus, is prone to political and present concerns rather than analytical and historical inquiry. Bearing this in mind, studies that are cognizant of, and even critically responsive to these concerns are much needed. Here, I would like to pay attention to a study that has real potential in this regard. After providing a short introduction on the theme, I will briefly respond to a recent talk by Sefer Soydar on the history of waqfs on the island, “Space and Society: Waqfs in urban and rural Ottoman Cyprus.”

Literally speaking, waqfs are endowments under Islamic law according to which various sources of revenue such as houses, fields, gardens, cash etc., were designated to finance a diverse set of religious, economic, and social functions. In this regard, these foundations had a manifold character that influenced the community at large. During the Ottoman era, hundreds, if not thousands, of waqfs were established more or less all over the island. Their founders were not necessarily and exclusively elite Muslim men as there was a considerable number of waqfs established and administered by women (Şensoy, 2019: 73) and, in some cases, by Christians (Korkmazer, 2021: 38). Notably, the properties of the Church of Cyprus were gradually integrated into the waqf framework. This process provided the high clergy, often registered as waqfs administrators in Ottoman documents, protection and autonomy in managing their assets while the Ottoman state secured their broader cooperation and consent. (Roudoumetof and Michael, 2010: 59-60)

To put it briefly, waqfs shaped the history of Cyprus for good, and beyond any religious/communal differences. Therefore, generating a genuine, multi-lingual, and comprehensive historical understanding is indispensable to assess how waqfs actually functioned beyond the communal differences and, of course, irrespective of their modern nationalist and anachronistic reproductions. Nevertheless, one comprehends that the recent quantitative increase of studies on waqfs of Cyprus barely corresponds to a qualitative advantage in forming such a historical perspective.

Among Turkish historians, the present-day discussions and historical studies on waqfs in Cyprus are heavily influenced by contemporary politics. Major historical research, sponsored and organised by the Turkish Republic starting from the second half of the 1990s, was shaped within the context of the Cyprus Question and negotiations around the property issue. Politically conditioned, it aimed for tracing, spotting and claiming the waqf lands and properties. Moreover, the Turkish nationalist paradigm represents Ottoman waqfs as unique mechanisms that generated and guarded the Turkish national identity on the island from the 16th century until today. In doing so, it carries a remarkable resemblance to the way the Greek nationalist history-writing interpreted the Church of Cyprus as the epitome of Greekness during the Ottoman rule on the island.

In parallel, a more recent paradigm consists of a ‘softer’ discourse that legitimises the historical and present existence of waqfs in a universal(ist) framework and, at the same time, sets out to increase their visibility among the Turkish Cypriot community. Accordingly, waqfs were represented as, first and foremost, centres of charity essentially and exclusively associated with social responsibility, philanthropy, goodness, kindness, humanity, peace, tolerance, animal rights, environmentalism, civil society. Needless to say, both paradigms were shaped by present-day concerns and terminology rather than an aim to put waqfs in their own historical context.

Sefer Soydar’s talk, titled“Space and Society: Waqfs in urban and rural Ottoman Cyprus,” is highly promising in this regard as he provides a trenchant critique of these two accounts and devotes himself to devising a new historical approach instead. Rather than approaching waqfs in a static and predetermined manner, he concentrates on the possibility of turning the institution of the waqf into an analytical tool to shed light on how they indeed organised the social and economic life as well as the urban and rural space in Cyprus.

Soydar, first of all, introduces “waqf community” as a concept to trace the communal relations and networks. This community consists of the founders, administrators and borrowers/tenants of the waqfs. It involves people from more or less every segment of the population on the island, such as Ottoman governors, Muslim religious personnel, Christian clergy, women, traders and peasants. Resting upon this, Soydar demonstrates various inter- and intra-communal relations between the local Muslims and Christians.

The Muslim ulema was the dominant group that administered the waqfs. Naturally, an imam, who was managing the cash waqfs in addition to his religious duties, assumed a new role in the credit relations as a money-lender who provided loans to people regardless of their religions. Likewise, the account register of the waqf of Selim II, the first waqf on the island, shows that in 1600-1601, about one-third of the waqf’s shops were used by non-Muslims (fig. 1). In another case, amongst countless others, the waqf of Ebubekir Paşa, which secured water flow in the rural part of Larnaca by building aqueducts, irrigation channels and wells, was renting the water to Feyzullah Efendi and Nikola, the son of Piri in a joint manner. (Altan, 1986: 488). In this sense, Soydar concludes that “waqf(s) not only redefined individuals (in the case of imams) on the island but also defined a novel community that came together because of the material conditions and daily needs of the period.”

Fig. 1: An Excerpt from the Account Book of the Waqf of Selim II

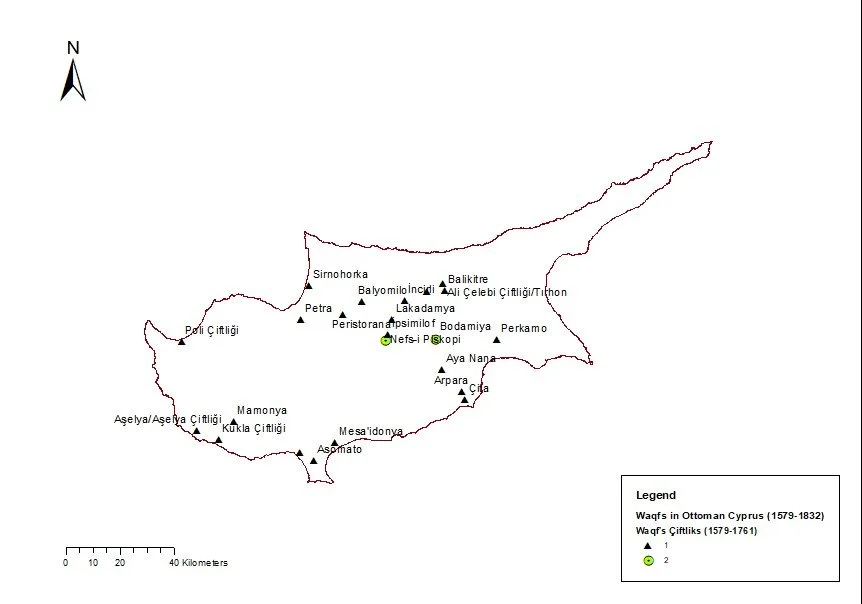

Resting on the activities of this waqf community, Sefer presents “waqf space” which waqfs (re)produced and (re)shaped, whether in urban areas by establishing mosques, inns, public baths, shops etc. or in rural areas by having an active role in agricultural production and establishing mills. Here, it must be noted that urban and rural areas are highly intertwined since, for example, waqf çiftliks along the island (fig. 2) and their agricultural revenues were used to develop and shape the landscape of urban towns and centres, most of all, Nicosia.

Fig. 2 Spatial distribution of waqf çiftliks throughout the island

Sefer’s application of Geographic Information Systems to trace the spatial distribution of cash waqfs and their activities proved illustrative since it visualised how much Nicosia dominated the waqf system on the island. (fig. 3) In an effort to explain this “Lefkoşalılık” (Nicosianness), Soydar integrates the term class habitus of Pierre Bourdieu and maintains that founding and maintaining a waqf is a practice of a social class. Such a practice represented a class-based culture and reinforced the dispositions and perceptions of a particular social status, or in Bourdieu’s words, “the represented social world, i.e. the space of lifestyles.” (Bourdieu, 1996: 170) Under this light, it is not surprising to see that the waqfs founders on the island disproportionately gathered in Nicosia. Such a concentration derived from their material wealth and, as Soydar points out, from the “privileged aura” of Nicosia walled city, which held a distinguished and protected status on the island following the Ottoman conquest. (Erdoğru, 2010: 631). In general, Soydar maintains that waqf is mainly an economic institution in which class habitus and elite solidarity were dominant. As a result, the Islamic ulema were the key figures and the main beneficiaries in this picture.

Fig. 3: Spatial distribution of the settlement of waqf founders on the island

Subsequently to Soydar’s talk, the Q&A section was particularly informative with regard to further questions and possible research on this theme. Thus, while I am concluding, a few remarks on possible future steps will not be entirely out of space. It seems that a comprehensive and historical understanding of the waqfs on Cyprus and their wide-ranging socio-economic activities on the island and beyond would enormously advance if and when: a) the existing and new archival material become easily accessible to researchers; b) new and better-organised ways of managing and interpreting innumerable sources and big amount of data will be practised efficiently; and, c) and perhaps most importantly, the researchers and historians of different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds will come together and create the conditions for a joint-initiative to trace the history of waqfs along the Balkans, the Middle-East and the Mediterranean islands through various perspectives based on multiple languages and archives.

Works Cited

Roudometof, Victor, and Michalis N. Michael. "Economic functions of monasticism in Cyprus: The case of the Kykkos Monastery." Religions 1.1 (2010): 54-77.

Altan, M. H. (1986). Belgelerle Kıbrıs Türk vakıflar Tarihi I-II: 1571-1974. Lefkoşa: Kıbrıs Vakıflar İdaresi.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A social critique of the judgment of taste. Harvard university press, 1987.

Erdoğru, M. A. (2010). XVI. yüzyıl sonlarında Lefkoşa şehri. XVI. Türk Tarih Kongresi 4, 427-448.

Şensoy, Fatma. (2019). "Kıbrıs Sicillerinden Kadınların Kurduğu Vakıf Örnekleri." Kıbrıs Araştırmaları ve İncelemeleri Dergisi 2.4: 61-74.

Written by Okcan Yıldırımtürk